This is the first part of my planned Renaissance Faire clothing. I say "Elizabethan" as there is apparently no evidence that hand-knitted stockings were worn quite so early as that in England, although I'm still waffling about their period authenticity. Up to the Elizabethan era at least, stockings and hose were commonly sewn from bias-cut fabric, a long and elaborately-shaped piece with a separate sole — one can only imagine the suprise when putting on a knitted one for the first time! like wearing leggings after years of wearing jeans.

One of the earliest known pairs of knitted stockings in Europe are part of Eleanora of Toledo's burial garments from 1562 (here is someone's pattern for them):

I have not done any serious research on Eleanora's stockings, so cannot be taken as an expert by any means, but I have to wonder if they were either simply not taking advantage of the stretchability of knitting at this point, or were so taken by the possibilities of patterned stitches that these were made rather larger than modern stockings would be. There is no record, of course, as to the size of Eleanora's calves, but the proportions look a little off to me.

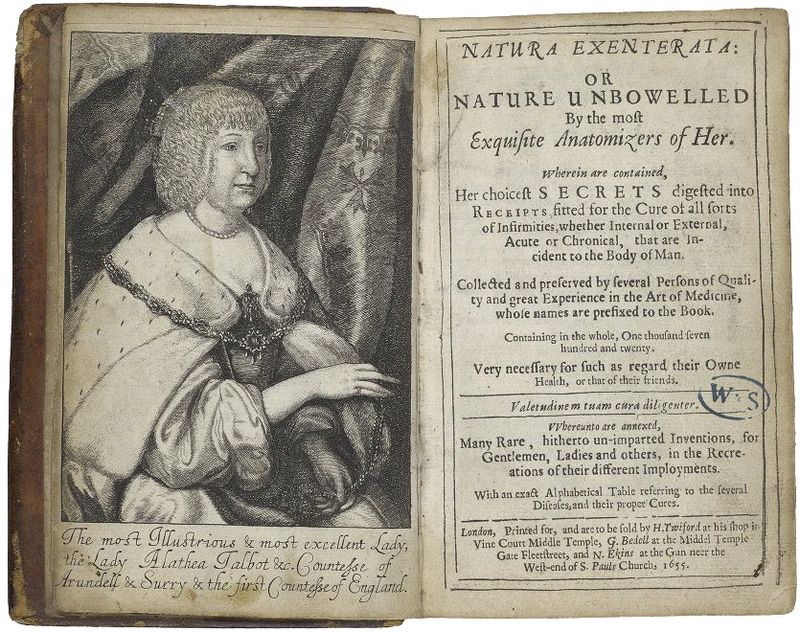

The earliest known pattern for knitted stockings is from a book called Natura Exenterata — "Nature unbowelled", that is, with all of her secrets spilled, as it were — from 1655.

(This copy is from the Folger Library) It is a book mostly of physicking, with shorter sections on household practices from horse-breeding to distilling, making perfumes, and so on, including how "To Dye divers kinds of Colours" which I found rather interesting — things like "To dye Popingay Greene. Take penny-hew and put it to Chamberlye or good Boockley, and seeth it and put it in the yeallow Yarne, and let it seeth, the longer it seetheth the deeper the colour will be." "Popinjay" is the old word for parrot, so I can only assume some sort of parrot-y green — chamberlye is, yes, urine from the chamber-pots, which apparently acts as a cleansing agent on the wool, removing oils and dirt, and it also apparently works in combination with the other dyestuff as both a pigment and a fixative.

Anyway —

The "knitting" bits in Exenterata can be found online at this University of Arizona page, under "Monographs" — I say "knitting" because there are only twenty pages included there and then only three actually related to "the order how to knit a hose", the rest being the dye recipes and a long section of netting patterns and another of lacework. (I get a kick out of one of the patterns, as the author says after every step that you should have x number of stitches "provided alwayes, if your work go true", that is, if you've done it right. I can't tell if that inspires confidence or not.)

There are quite a variety of opinions around as to whether or not knitted stockings, despite the difference between dates of Eleanora's obviously expertly-knitted stockings and the Exenterata pattern, are really "period" when talking about Elizabethan costuming. The Exenterata pattern gives instruction on shaping the calf and turning the heel, but stops at the toe, making me think that this must have been common knowledge by 1655, enough that it wasn't thought necessary to include that part, and the novelty, if any, is in the heel and foot. Actually, I think you could find opinions these days for either date, even among the really dedicated SCA folks, but I am willing to be corrected, my philosophy being, as someone once said, "To stonde alwaies stiff and obstinate in one opinion is rather Vice than Vertue".

For mine, I was really just making it up as I went along, according to my brief and limited research. Ribbing was not known until quite some time later, so the top of a stocking was a simple one of garter stitch, or perhaps a fancier cuff like Eleanor's, to be folded over or not as the case may be. The stockings were held up with separate garters, either a knitted strip of garter stitch (hence the name), a piece of fabric, or a woven strip such as from tablet-weaving. Knitted stockings were made to imitate the sewn ones by including a "seam" down the back — I used a simple one-stitch purled line, but apparently a wider version can be found.

The yarn is two lovely skeins of Shepherd Sock in Natural, a delight to work with, and the pattern is custom-fitted with help from the Arachne Sock Calculator.

I think that the only thing I would do differently is to move the center of the clock towards the back by 2 stitches, so that it lines up with the edge of the heel flap. If I'd thought about it more thoroughly, I probably would have realized that the center of the side is two stitches towards the instep, and not in line with the gusset decreases. (Smacks forehead.)

The heel is the "common shaped heel" from Nancy Bush's Folk Socks book, which is I think essentially the same as the Exenterata one. The only modification I made from Bush's version was to not cut the yarn but simply use a three-needle bind-off instead of grafting the bottom-of-the-heel stitches. Yes, I know, I thought "a bind-off on the bottom of the foot!" too, but I was going more for historical accuracy, as grafting apparently wasn't known for quite some years more, and as it happens, at this gauge and for so short a length as this, I can't feel it at all.

This is how the heel looks in progress from the inside — the line of knit stitches is the "seam", then the three-needle bind-off goes on up to where the needles meet —

I used the round toe — it seems that a wedge toe was more commonly used in early hand-knitted stockings, with a three-needle bind-off, but that seam, I think, you would feel more easily than one at the bottom of your heel, and so the second-earliest option won out.

And so — as far as a Faire gown is concerned anyway, I've had my fling with knitting — on to sewing!

Leave a comment